Major Revision vs Minor Revision: Timeline, Meaning & Response Strategy

Major revision vs minor revision in a journal decision describes the editor’s assessment of a manuscript’s scientific readiness for publication. A major revision indicates that the work has merit but requires substantive methodological, analytical, or conceptual improvements before it can be reconsidered. A minor revision signifies that the study meets the journal’s standards, with only limited clarifications, formatting adjustments, or minor interpretive refinements needed. While both decisions keep the manuscript under active consideration, they differ markedly in editorial confidence, revision scope, and probability of acceptance. This article explains how editors apply these labels, how reviewers interpret them, and how experienced authors respond to secure acceptance efficiently.

Many authors struggle to understand what these editorial decisions actually signify. Does a major revision mean your manuscript has serious problems, or is it simply standard practice for the journal? Does a minor revision guarantee acceptance if you make the requested changes? How much revision is too much revision? These questions matter because your response strategy should differ substantially based on which type of revision you’ve received.

As someone who has navigated both types of revision decisions and evaluated them as a manuscript reviewer, understanding how editors make final decisions helps explain these categories. I shall explain what editors and reviewers expect in each case, and how to respond strategically to maximize your chances of acceptance. Understanding these differences transforms revision from an anxious ordeal into a manageable process with clear expectations.

Quick Navigation:

- Major vs Minor Revision Comparison Table

- What Is Major Revision?

- What Is Minor Revision?

- What Does “Pending Major Revision” Mean?

- Key Differences Explained

- Response Strategy for Each Type

- FAQ

Quick Comparison: Major vs. Minor Revision at a Glance

| Factor | Major Revision | Minor Revision |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of Changes | Substantial modifications required | Small improvements needed |

| Typical Requests | New analyses, restructuring, expanded sections | Clarifications, formatting, minor additions |

| Timeline Expected | 8-12 weeks (2-3 months) | 2-4 weeks (4-8 weeks max) |

| Reviewer Re-evaluation | Yes, full re-review | Often editor-only review |

| Acceptance Likelihood | 70-85% if addressed well | 85-95% with proper response |

| Work Required | Significant effort, possibly new data | Moderate effort, refinement |

| Response Letter | Detailed, point-by-point justification | Straightforward acknowledgment |

| Common Outcome | Accept or additional minor revision | Accept with corrections |

| Red Flags | Contradictory comments, scope concerns | None if addressed thoroughly |

This table provides immediate context, but the nuances within each category require deeper explanation to guide your response strategy effectively.

What Is Major Revision?

Major revision represents an editorial decision indicating that your manuscript has potential for publication but requires substantial improvement before acceptance can be considered. This decision sits between outright rejection and acceptance, signaling that while the work shows promise, significant concerns must be addressed through thorough revision.

Definition and Editorial Intent

When editors issue major revision decisions, they’re communicating several things simultaneously. They believe your research contributes something valuable to the field—otherwise, they would have rejected the manuscript outright. They’ve identified significant problems that prevent acceptance in the current form, but these problems appear fixable through revision rather than fundamental flaws that revision cannot address. They’re willing to invest additional editorial and reviewer time in your manuscript, which represents genuine interest rather than perfunctory processing. For detailed editorial guidelines, see SAGE Publishing Author Guidelines

The major revision category exists because journals need a middle ground between rejection and acceptance. Not every manuscript arrives ready for publication, but many can reach that standard with substantial author effort. Major revision creates space for this improvement process while managing author expectations about the work required.

Common Major Revision Requests

Understanding what typically triggers major revision decisions helps you assess whether your manuscript’s issues are typical or unusually problematic. Our comprehensive guide on how to respond to peer review comments

provides detailed strategies for addressing each type of request.

Methodological concerns requiring additional analysis represent one of the most frequent major revision triggers. Reviewers might request new statistical tests to verify conclusions, additional experimental conditions to rule out alternative explanations, sensitivity analyses to test result robustness, or validation with different datasets or approaches. These requests require actual new work rather than simple rewriting.

Substantial restructuring of manuscript organization often appears in major revision decisions when reviewers find the current structure confusing or illogical. This might involve reorganizing sections to improve logical flow, splitting overly long sections into clearer components, moving material between introduction, methods, results, and discussion, or creating new sections to address topics inadequately covered.

Significant expansion of the literature review or discussion becomes necessary when reviewers identify gaps in your engagement with existing research or insufficient interpretation of findings. Major revision might require incorporating substantial additional citations, addressing competing theories or contradictory findings you ignored, expanding discussion of implications or limitations, or connecting your work more explicitly to ongoing debates in the field.

Clarification of contribution or novelty requires rethinking how you frame your work’s significance. Reviewers sometimes struggle to understand what’s genuinely new in your research, requiring you to rewrite introduction and discussion to make the contribution explicit, differentiate your approach from similar existing work, or better articulate why your findings matter to the field.

Addressing fundamental interpretation concerns happens when reviewers question whether your data support your conclusions. This might require reconsidering claims that overstate your evidence, acknowledging alternative interpretations of results, providing additional evidence for contested claims, or moderating conclusions to match what your data actually demonstrate.

Timeline Expectations for Major Revision

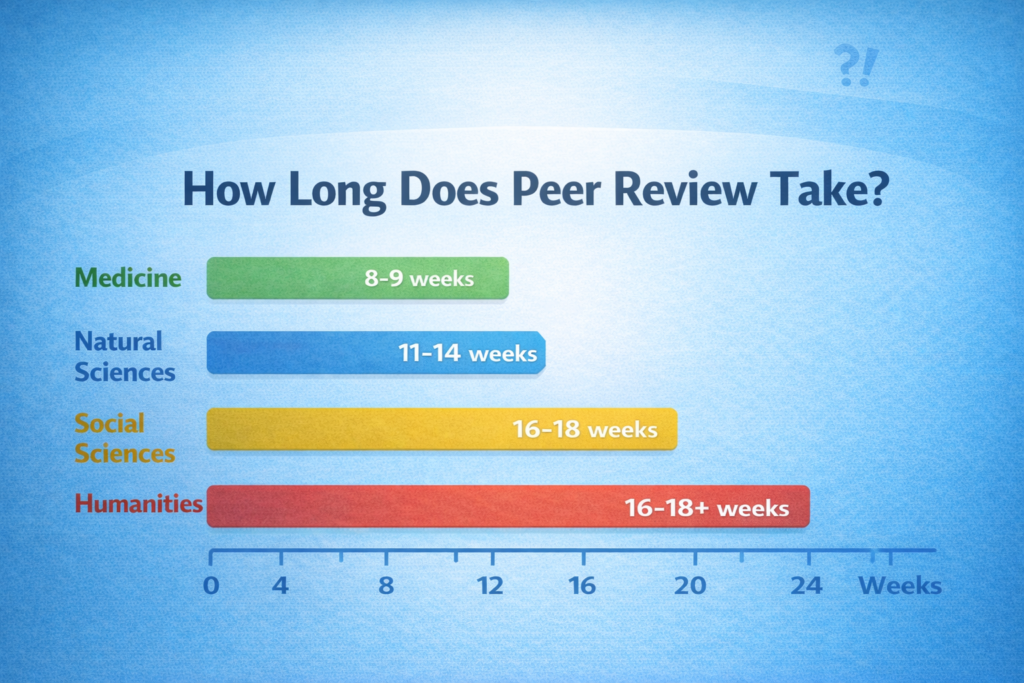

Journals typically allow 8-12 weeks for major revision completion, with some journals permitting up to 16 weeks for particularly extensive revision requests. This timeline reflects recognition that a major revision requires substantial work that authors must fit around other professional responsibilities. Understanding how long peer review takes helps you plan

realistic timelines for completing revisions.

The timeline breaks down roughly as follows: one to two weeks for careful reading and assessment of reviewer comments, four to eight weeks for conducting the actual revision work, including any new analyses or substantial rewriting, one to two weeks for co-author review and approval of revisions, and one week for preparing the detailed response letter and formatting materials for resubmission.

Requesting extensions is acceptable when circumstances warrant. Most journals grant reasonable extension requests when authors communicate proactively before deadlines. Valid reasons include legitimate need for additional time to conduct requested new analyses, coordination challenges with multiple co-authors across institutions, unexpected professional or personal circumstances, or revision requests that genuinely require more time than initially allocated.

The key to successful extension requests is early, professional communication explaining specifically why more time is needed and proposing a realistic new deadline. Avoid vague requests for undefined extensions or requests made only after deadlines have passed.

Acceptance Rates Following Major Revision

Research on editorial outcomes and patterns observed across multiple journals suggests that 70-85% of manuscripts receiving major revision decisions eventually achieve acceptance, though this varies by field and journal. This relatively high success rate when authors thoroughly address concerns demonstrates that major revision truly represents an opportunity rather than rejection in disguise.

The manuscripts that fail after major revision typically fall into several patterns: authors inadequately address reviewer concerns, treating revision superficially rather than thoroughly; requested changes reveal additional problems that weren’t apparent in initial submission; authors fundamentally disagree with reviewers but fail to provide compelling justification for their position; or revision takes so long that the research becomes outdated or scooped by other publications.

The critical factor determining success is how seriously authors take the revision process. Thorough, thoughtful revision that genuinely engages with reviewer concerns succeeds at high rates. Perfunctory revision that technically responds to comments without substantively improving the manuscript often leads to rejection after revision.

What Does “Pending Major Revision” Status Mean?

If you’re checking your submission portal and see “Pending Major Revision” as the status, this is simply an administrative label indicating your manuscript is awaiting the formal decision letter—not the decision itself.

What’s happening behind the scenes:

- The editor is finalizing reviewer comments and writing the decision letter

- The system has moved your manuscript into the revision workflow queue

- Administrative processing is underway (typically 1-7 days)

Common questions about this status:

How long does “pending” last?

Typically 1-7 days, occasionally up to 2 weeks for journals with manual processing or editor availability issues.

Should I be worried?

No. This is normal administrative processing. The decision has essentially been made; you’re just waiting for the formal notification.

When should I contact the editor?

Only if the status remains “pending” for more than 3 weeks without explanation. Before that, simply wait for the decision email.

What should I do while waiting?

- Review your manuscript with fresh eyes

- Start mentally preparing for likely reviewer comments

- Don’t make any changes yet until you receive official feedback

What Is Minor Revision?

Minor revision represents a very positive editorial decision, indicating that your manuscript is nearly ready for publication with only small improvements needed. This decision signals a strong interest in publishing your work with minimal additional changes.

Definition and Editorial Intent

When editors request minor revisions, they’re communicating that your manuscript meets publication standards in its fundamental aspects—research quality, contribution significance, methodological rigor—but requires refinement in presentation, completeness, or clarity. The issues identified don’t question your core findings or approach but rather point to areas where small improvements would strengthen the final published version.

Minor revision decisions reflect the editor’s confidence in eventual acceptance. The required changes are typically straightforward enough that editors may review revised manuscripts themselves rather than sending them back to external reviewers. This streamlined process signals that the revision is expected to be routine rather than requiring fresh expert evaluation.

Common Minor Revision Requests

Understanding typical minor revision requests helps you gauge whether your revision requirements are standard or unusually extensive for this category.

Clarification of specific statements or findings represents the most common minor revision request. Reviewers might ask you to clarify ambiguous wording that could be misinterpreted, explain technical terms or abbreviations for a broader readership, provide additional detail about specific methodological choices, or rephrase conclusions to more precisely match your evidence.

The addition of limited references or citations addresses gaps where important related work wasn’t cited. Minor revision might require adding several recent relevant citations, including specific papers reviewers mention, citing foundational work in your area that was overlooked, or acknowledging limitations or alternative approaches discussed in existing literature.

Minor formatting or presentation improvements make the manuscript more readable and professional. This includes improving figure quality or labeling, adjusting table formats for clarity, correcting citation formatting inconsistencies, fixing grammatical errors or typos, or reformatting sections to match journal style.

Small additions to the discussion or limitations strengthen the interpretation without requiring new analyses. Reviewers might request a brief discussion of study limitations you didn’t explicitly acknowledge, a short commentary on how findings relate to specific other work, acknowledgment of alternative interpretations, or a minor expansion of implications or future directions.

Addressing technical corrections includes fixing errors that don’t affect conclusions but need correction for accuracy. This might involve correcting specific numbers or values if errors exist, fixing reference citations, adjusting terminology for consistency, or clarifying methodological descriptions where ambiguity exists.

Timeline Expectations for Minor Revision

Journals typically expect minor revision completion within 2-4 weeks, with some allowing up to 8 weeks. The shorter timeline reflects the limited scope of work required—minor revisions shouldn’t demand extensive new writing or analysis.

The revision process should proceed quickly: a few days to carefully read and understand all comments, one to two weeks for making the requested changes and preparing a response, a few days for co-author review if needed, and final formatting and submission.

The turnaround advantage of completing minor revisions quickly is that it keeps your manuscript moving through the publication pipeline without delay. Slow response to minor revision creates unnecessary postponement of acceptance and publication without any strategic benefit.

Acceptance Rates Following Minor Revision

Minor revision decisions convert to acceptance at rates of 85-95% when authors properly address all requested changes. The very high success rate reflects that editors issue minor revision decisions only when they’re confident the manuscript will be acceptable after small improvements.

The small percentage that fails after minor revision typically involves situations where authors overlook or inadequately address seemingly small comments that editors or reviewers consider important, where authors make changes that introduce new errors or problems, where authors argue extensively against minor requests rather than simply addressing them, or where the revision reveals issues that weren’t apparent in the initial review.

The key to success with minor revision is treating every comment seriously, even when changes seem small. Editors requested these revisions for reasons, and dismissing any comment as unimportant risks undermining the otherwise strong position your manuscript holds.

Key Differences Explained in Depth

While the comparison table provides an overview, understanding the distinctions more deeply helps you interpret what your revision decision means and how to respond effectively.

Scope and Depth of Changes Required

The fundamental difference between major and minor revisions lies in how extensively you must modify the manuscript. Major revision typically requires rethinking substantial portions of your work—reanalyzing data, restructuring arguments, expanding insufficient sections, or fundamentally reconsidering how you’ve framed your contribution. These changes demand significant intellectual effort and time, often requiring you to revisit your research process rather than simply improve how you describe completed work.

Minor revision focuses on refinement and polish rather than reconceptualization. The changes improve presentation, clarify ambiguities, fill small gaps, or correct errors, but they don’t require you to rethink your fundamental approach. You’re enhancing an already solid manuscript rather than substantially rebuilding it.

The practical test: If addressing the requested changes requires more than 40 hours of work, you’re dealing with a major revision, even if the editor labeled it differently. If you can complete everything in 20 hours or less, it’s genuinely minor.

Acceptance Likelihood and Editorial Confidence

Major revision signals cautious optimism—editors see potential but aren’t yet confident in acceptance. The extensive changes required mean the revised manuscript might look substantially different, creating uncertainty about whether the revision will adequately address concerns. Editors are essentially saying, “This could work, but we need to see significant improvement before making commitments.”

Minor revision signals strong confidence—editors have essentially decided to accept pending small improvements. The limited scope of changes means the revised manuscript will remain fundamentally the same, just polished. Editors are saying, “We want to publish this, just make these small fixes first.”

From the reviewer’s perspective, when I recommend a major revision, I’m genuinely uncertain whether the revision will satisfy my concerns until I see the revised version. When I recommend a minor revision, I’m confident the author can address my comments, and I expect to recommend acceptance after checking that they did so.

Timeline Expectations and Pressure

Major revision timelines of 8-12 weeks acknowledge that substantial work takes time. Authors shouldn’t feel pressured to rush major revisions—thoroughness matters more than speed. Journals expect you to need weeks or months to properly address significant concerns.

Minor revision timelines of 2-4 weeks create gentle pressure for a relatively quick turnaround. Journals expect minor revisions to proceed quickly because the work required is limited. Slow response suggests either you’re not prioritizing the manuscript or you’re finding the “minor” changes more difficult than editors expected, both of which might concern them.

Strategic timing: For a major revision, take the time you need to do thorough work. For minor revision, respond as quickly as you reasonably can without sacrificing quality—rapid turnaround signals enthusiasm and professionalism.

Reviewer Re-Involvement and Re-Evaluation

Major revision almost always involves sending the revised manuscript back to the original reviewers for re-evaluation. Reviewers will check whether you adequately addressed their concerns, evaluate whether new analyses or expansions satisfy their requests, and assess whether the revised manuscript now meets publication standards. This creates an opportunity for reviewers to identify new concerns or remain unsatisfied with your revisions.

Minor revisions often bypass external re-review, with editors checking revisions themselves. This accelerated process reflects the editor’s confidence that the changes are straightforward enough that they can verify completion without needing external expertise again. It also eliminates the risk of reviewers raising new concerns in subsequent rounds.

The re-review risk with major revision means you’re not guaranteed acceptance even after extensive work. You’re resubmitting to a fresh evaluation, not simply checking boxes. This reality requires taking revision extremely seriously rather than treating it as a formality.

How Your Response Strategy Should Differ

Understanding major vs. minor revision isn’t just academic—it should fundamentally change how you approach the revision process.

Response Strategy for Major Revision

Mindset shift required:

Treat this as a serious research opportunity, not a formatting exercise. You’re being asked to substantially improve your work, which often makes it stronger even if the process feels demanding.

Response letter approach:

- Write detailed, point-by-point responses (typically 5-15 pages)

- Quote each reviewer comment exactly before responding

- Provide specific manuscript locations for every change (page/line numbers)

- Justify any disagreements with evidence, not emotion

- Include before/after examples for major changes

Time allocation:

- Week 1: Read all comments multiple times, create revision plan

- Weeks 2-8: Execute substantive changes (new analyses, restructuring)

- Weeks 9-10: Co-author review and refinement

- Weeks 11-12: Response letter preparation and final checks

Common mistakes to avoid:

- Superficial changes that don’t truly address core concerns

- Arguing extensively without providing evidence

- Missing the forest for the trees (addressing details but not big-picture issues)

- Submitting rushed revisions just to meet deadlines

Response Strategy for Minor Revision

Mindset shift required:

You’re in excellent position—don’t jeopardize it with carelessness. Every small comment matters because acceptance is nearly guaranteed if you’re thorough.

Response letter approach:

- Concise but complete (typically 2-5 pages)

- Acknowledge each comment professionally

- Confirm completion with specific locations

- Don’t over-explain or justify excessively

- Simple, direct, respectful tone

Time allocation:

- Days 1-3: Read comments, create checklist

- Week 1-2: Make all requested changes

- Week 3: Co-author quick review

- Week 4: Final formatting and submission

Common mistakes to avoid:

- Treating any comment as “too minor” to address properly

- Taking so long that editors wonder about your commitment

- Introducing new errors while fixing old ones

- Arguing against simple requests instead of just complying

When Revision Type Is Ambiguous

Sometimes the revision label doesn’t match the actual work required. If your “minor revision” requests seem to require 50+ hours of work, or if your “major revision” only asks for small clarifications:

- Trust the work scope, not the label for planning purposes

- Respond as if it’s major revision if you’re uncertain (better to over-prepare)

- Contact the editor if truly confused about expectations: “I want to ensure I understand the scope of changes expected. The decision letter indicates [X], but the specific requests seem to require [Y]. Could you clarify your expectations for the revision?”

How to Handle Major Revision Strategically

Receiving a major revision requires careful strategic thinking about whether and how to revise, followed by thorough execution if you proceed.

Initial Assessment: Is This Revision Worth Doing?

Not every major revision invitation warrants accepting. Before diving into revision, conduct an honest assessment of several factors. Sometimes it’s better to submit to a different journal rather than revise extensively for a poor-fit venue.

Can you realistically address all concerns? Some revision requests require resources, data, or expertise you don’t have. Requesting additional experiments might be impossible if you no longer have access to the necessary facilities. Requesting analyses of data you don’t possess cannot be fulfilled. Requesting expertise outside your competence might require adding co-authors or might simply be infeasible.

Do reviewer requests make sense? Sometimes reviewers ask for things that demonstrate a misunderstanding of your work, request analyses inappropriate for your research design, or want changes that would actually harm rather than improve the manuscript. If you fundamentally disagree with core reviewer concerns and cannot provide compelling justification for your original approach, revision might not succeed.

Is the timeline realistic? Consider your other commitments over the coming weeks and months. If you’re teaching full course loads, handling multiple other manuscripts, facing grant deadlines, or dealing with personal circumstances, completing a major revision adequately might be impossible within the journal’s timeline.

Is this journal still your best option? Sometimes major revision reveals that your work doesn’t fit this journal as well as you thought. If scope concerns emerged or if you’d need to substantially alter your manuscript to satisfy this journal’s expectations, submitting elsewhere might better serve your work.

If your assessment concludes that revision isn’t worthwhile or feasible, withdrawing and submitting to a more appropriate journal is a legitimate strategy. Don’t waste months on revision that likely won’t succeed or that requires compromising your work in ways you’re uncomfortable with.

Creating Your Revision Strategy

If you decide to proceed, develop a systematic plan before beginning actual revision work.

Categorize all reviewer comments into themes or types. Group related comments together, even if they came from different reviewers. Identify which comments require new analyses, rewriting, restructuring, or minor additions. Distinguish between comments you agree with versus those requiring thoughtful response or pushback.

Prioritize the most substantial changes for early attention. Begin with requests that might reveal new problems or require significant time, such as new statistical analyses or experiments. This allows you to identify any deal-breakers early rather than discovering late in revision that you cannot adequately address a major concern.

Create a detailed revision timeline, allocating specific time blocks to different tasks. Estimate how long each major change will require and schedule that work realistically around your other commitments. Build in buffer time for unexpected complications or longer-than-expected tasks.

Assign responsibilities clearly if working with co-authors. Determine who will handle which revision requests, who will draft the response letter, and who will review the final revised manuscript. Coordinate timelines to ensure everyone can complete their portions without becoming a bottleneck.

Executing Major Revision Effectively

Address every single reviewer comment explicitly in your revision and response letter. Even if a comment seems minor or you disagree with it, acknowledge and respond to it. Ignored comments create an impression of incomplete revision regardless of how much work you actually did.

Go beyond minimum compliance when addressing major concerns. If reviewers questioned your methodology, don’t just add a sentence defending it—add substantial justification with citations, consider conducting sensitivity analyses even if not explicitly requested, or acknowledge limitations transparently. Exceed expectations rather than merely meeting them.

Restructure substantially if needed rather than making minimal adjustments. If multiple reviewers found sections confusing or poorly organized, invest time in genuine restructuring rather than minor reordering. Substantial improvement impresses reviewers more than grudging minimal changes.

Prepare a meticulous response letter documenting exactly what you changed and why. Use a point-by-point format, addressing every comment with specific manuscript locations showing where you made changes. Explain your reasoning for any decisions reviewers might question. The response letter often matters as much as the revision itself in demonstrating that you took concerns seriously.

How to Handle Minor Revision Efficiently

Minor revision requires a different approach focusing on efficiency, thoroughness, and avoiding overcomplicated changes.

Quick Turnaround Strategy

Respond promptly to minor revision requests when possible. Completing revision within two to three weeks demonstrates professionalism and enthusiasm. It keeps your manuscript moving toward publication without unnecessary delay.

Don’t overthink simple requests. If reviewers ask for clarification, provide it directly without extensive reanalysis of whether the original wording was actually unclear. If they want additional citations, add them without questioning whether they’re truly necessary. Minor revision isn’t the place for extensive deliberation—it’s the place for efficient execution.

Work systematically through all comments using a checklist approach. Mark each comment as you address it to ensure nothing gets overlooked. Small oversights in minor revisions can unnecessarily delay acceptance.

Avoiding Over-Revision

One mistake authors make with minor revision is using it as an opportunity to extensively revise beyond what was requested. While good intentions drive this, it creates risks.

Don’t substantially rewrite sections that weren’t flagged as problematic. Extensive unrequested changes can introduce new errors or inconsistencies that complicate editorial review. They also make it harder for editors to verify that you addressed specific requests when they’re lost in a sea of other changes.

Don’t add extensive new content unless specifically requested. A minor revision requesting two additional citations doesn’t need you to add ten citations and two new paragraphs. Excess additions might actually weaken your manuscript by diluting focus or introducing tangential material.

Focus on requested changes and resist the temptation to “improve” everything. Trust that the manuscript was already nearly ready for publication—that’s why you received a minor revision rather than a major revision or rejection.

Response Letter for Minor Revision

Minor revision response letters should be brief and straightforward rather than extensively detailed. Editors and reviewers don’t need elaborate justification for small changes—they need confirmation that you made them.

Use simple format: “Thank you for the helpful comments. We have addressed all points as follows:” Then list each comment with brief confirmation: “We have clarified this wording as suggested (page 5, line 112)” or “We have added the requested citation (Reference 24, page 6).”

Keep the response letter under two pages for typical minor revisions. Extensive response letters for minor revisions suggest either that the revision wasn’t actually minor or that you’re over-explaining simple changes.

Real Examples: Major vs. Minor Revision Scenarios

Concrete examples illustrate how these revision types differ in practice. Some revision requests are better understood as revise and resubmit decisions, which we explore in detail.

Major Revision Example

Research Context: A manuscript examining the relationship between workplace flexibility policies and employee productivity using survey data from 200 companies.

Reviewer 1 Comments:

- The sample size seems small for drawing general conclusions about all companies. Can you expand the sample or provide a power analysis justifying the current size?

- The productivity measures rely only on self-reports. This creates potential bias. Can you incorporate objective productivity metrics?

- The discussion doesn’t adequately address the Jones et al. (2023) study that found opposite results in manufacturing settings.

Reviewer 2 Comments:

- The causal language in your conclusions overstates what correlational data can show. Please revise to make claims match your methodology.

- The flexibility policies are treated as uniform, but they likely vary considerably. Can you provide a more nuanced analysis of different policy types?

- Several recent relevant papers aren’t cited [lists 5 papers].

Why This Is a Major Revision:

- Requires potential new data collection or analysis

- Needs methodological expansion (objective metrics, power analysis)

- Requires substantial revision of the discussion and conclusions

- Demands reconceptualization of how variables are measured

- Timeline needed: 8-12 weeks minimum

Appropriate Author Response: The authors would need to conduct power analysis and explain sample size limitations clearly, acknowledge self-report limitations, and ideally add objective productivity data if accessible, substantially expand discussion addressing contradictory findings, revise all causal language to match correlational methodology, and analyze policy types separately rather than treating them as a uniform category.

Minor Revision Example

Research Context: Same manuscript after successful major revision, now in second review round.

Reviewer 1 Comments:

- The revised power analysis is convincing. Just clarify in the methods section (page 8) what alpha level you used.

- Figure 2 is difficult to read—can you increase the font size and adjust colors for better contrast?

- On page 12, line 267, you mention “significant effects” but should specify the p-value.

Reviewer 2 Comments:

- The revised discussion addresses my concerns well. One small addition: please cite the Martinez and Lee (2024) paper that also examined policy variation—it supports your findings.

- The conclusion section could benefit from one sentence acknowledging the generalizability limitations given your sample characteristics.

Why This Is a Minor Revision:

- No new analysis required

- All requests involve clarification or small additions

- No fundamental concerns about approach or conclusions

- Changes can be completed in days

- Timeline needed: 2-4 weeks maximum

Appropriate Author Response: The authors would clarify the alpha level in one sentence, improve Figure 2 formatting, add specific p-values where mentioned, add the requested citation, and add one sentence about generalizability limitations. Total work: perhaps 6-8 hours, including response letter preparation.

Frequently Asked Questions About Major and Minor Revisions

What does “define:major+revision” mean?

This is a Google search operator some researchers use to find the specific definition of major revision. A major revision means substantial changes are required to your manuscript’s methodology, analysis, structure, or argumentation—typically requiring 8-12 weeks of work with a 70-85% eventual acceptance rate.

What is the exact meaning of “minor revision” in academic publishing?

Minor revision means your manuscript is nearly ready for publication with only small improvements needed—typically clarifications, formatting fixes, or limited additions. It signals 85-95% likelihood of acceptance if you properly address all comments within the typical 2-4 week timeline.

Is “decision in process” the same as major or minor revision?

No. “Decision in process” is a status indicating the editorial team is actively reviewing your manuscript or making their decision. It precedes the actual revision decision. Once the decision is made, the status changes to “major revision,” “minor revision,” or another outcome.

How do I know if my revision request is actually major or minor?

Look at the scope: If you need more than 40 hours of work, new data analysis, or substantial restructuring—it’s truly major. If you can complete everything in 20 hours or less with no new data—it’s genuinely minor, regardless of the label used.

Can a major revision become a rejection?

Yes. Approximately 15-30% of major revisions result in eventual rejection, typically because authors inadequately address concerns, revision reveals new problems, or authors can’t provide compelling justification for disagreements with reviewers.

What’s the difference between “revise and resubmit” and major revision?

“Revise and resubmit” typically means your manuscript must go through the full review process again with no guarantee of acceptance. Major revision usually stays with the same editor and reviewers with higher acceptance probability if you address concerns thoroughly.

Does a major revision mean my paper has serious problems?

Not necessarily. Major revision is standard practice at many journals, even for solid research. It indicates that substantial improvement is needed, but it also signals the editor’s confidence that revision can succeed. Many excellent papers go through major revision before acceptance. The key is whether the requested changes are reasonable and addressable—serious problems would typically result in rejection rather than revision invitation.

Can a major revision turn into rejection?

Yes, approximately 15-30% of major revisions ultimately result in rejection, either because authors inadequately address reviewer concerns, revision reveals additional problems, or reviewers remain unsatisfied even after revision. However, thorough revisions that genuinely engage with concerns succeed at high rates. The risk of rejection after revision emphasizes the importance of taking revision requests seriously rather than treating them as a formality.

Should I disagree with reviewers if I think they’re wrong?

Yes, when you have a strong justification. Reviewers sometimes misunderstand your work or suggest changes that would harm rather than improve your manuscript. Reasoned disagreement is acceptable when accompanied by a clear explanation and supporting evidence. However, choose your battles wisely—disagreeing with minor points wastes goodwill, while disagreement on fundamental issues might be necessary to maintain your work’s integrity.

How detailed should my response letter be?

For major revision, very detailed—typically 5-10 pages addressing every comment with specific manuscript locations and thorough justification. For minor revision, brief—usually 1-2 pages with straightforward confirmation of changes. The response letter demonstrates your engagement with reviewer concerns, so invest appropriate effort based on the revision scope.

Can I request an extension for the revision deadline?

Yes, most journals grant reasonable extension requests. Contact the editorial office 2-4 weeks before your deadline, explain briefly why you need more time, and propose a specific new deadline. Legitimate reasons include needing time for requested new analyses, co-author coordination across institutions, or unexpected professional circumstances. Avoid vague requests or requests made only after deadlines pass.

What if reviewers disagree with each other?

This happens frequently. Your response letter should acknowledge both perspectives and explain how you addressed or mediated between conflicting suggestions. Sometimes you can satisfy both reviewers with careful framing. Other times, you’ll need to choose one approach and explain why, being respectful of both viewers’ perspectives.

Is a minor revision basically guaranteed acceptance?

Nearly, but not quite. Minor revision converts to acceptance at 85-95% rates when authors properly address all comments. The small failure rate typically involves overlooked comments, poor execution of changes, or introduction of new problems. If you address every request thoroughly, acceptance is highly likely.

How do I know if my “minor revision” is really minor?

Check the scope of requested changes. Genuine minor revisions require limited additions or clarifications, no new analyses or data collection, minimal restructuring, and can realistically be completed within 2-4 weeks. If requests seem more extensive, contact the editorial office for clarification about timeline expectations and whether additional substantial work is anticipated.

Key Takeaway

The distinction between major and minor revision carries significant implications for the work required, timeline expected, and likelihood of eventual acceptance. Major revision represents a genuine opportunity for substantial improvement of manuscripts with publication potential, requiring thorough engagement with reviewer concerns over weeks or months. Minor revision signals strong editorial interest in publishing your work pending small refinements that can typically be completed in days or weeks.

Your response strategy should match the revision type you’ve received. Major revision demands careful assessment of feasibility, strategic revision planning, thorough execution addressing every concern, and meticulous documentation of changes. Minor revision requires efficient turnaround, focused attention on requested changes without over-revision, and streamlined response documentation.

Understanding these differences transforms revision from an anxiety-inducing ordeal into a manageable process with clear expectations. Both revision types represent positive outcomes compared to rejection—they indicate editorial interest in publishing your work. The key to success lies in taking revision seriously, responding appropriately to the scope of changes requested, and documenting your work thoroughly in response letters that demonstrate genuine engagement with reviewer feedback.

About the Author

This guide was written by Dr. James Richardson, a research engineer with experience in academic publishing and peer review across multiple journals. The insights on revision types reflect both navigating these decisions as an author and evaluating revision adequacy as a manuscript reviewer.

Questions about your revision decision? Leave a comment below.

Last updated: January 2026 | Based on editorial practices and revision outcome patterns

Pingback: How to Respond to Peer Review Comments Effectively - ije2.com

Pingback: Is Revise and Resubmit Worth It? Success Rates & What to Expect - ije2.com

Pingback: How Journal Editors Make Decisions: Inside the Editorial Process (What Increases Your Chances) - ije2.com

Pingback: What to Do After Manuscript Rejection: Complete Guide (2026) - ije2.com

Pingback: "Under Review" Status: What's Happening & How Long (2026) - ije2.com

Pingback: 15+ Professional Alternatives to "We Respectfully Disagree" - ije2.com